Glimpses of Indonesian History in four objects

By Jarrah Sastrawan

History doesn’t just live in textbooks and dusty archives. Physical objects and artworks carry with them their own stories that can give us surprising insights into the past, as shown by the BBC and British Museum’s recent hit exhibition A History of the World in 100 Objects (2016). These four objects from Indonesia offer new perspectives on the country’s history. Each is a beautiful work of art that reflects its own historical context, but together, they show that Indonesia has always been deeply diverse, and strongly connected to the rest of the world.

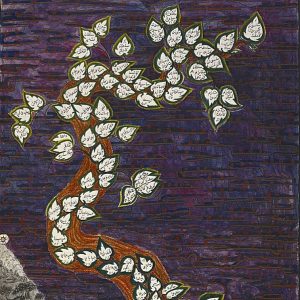

1. A Family Tree of Javanese Kings

An illustration of the family tree of the central Javanese sultanates, all the way from Adam at the root to the Pakubuwana and Hamengkubuwana dynasties at the leaves. This page is found in a British Library manuscript of a genealogical text written in Malay but copied in Demak, coastal Java, in 1814. It’s a common feature of classical Indonesian historical texts that they organise time using genealogy rather than dates, so that events in the narrative are attached to particular generations rather than years of an era. This feature led modern scholars to unfairly dismiss the validity of traditional histories, because they assumed that a dated chronology is a prerequisite for accurate historical writing.

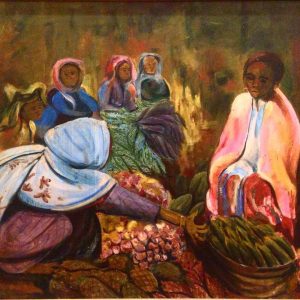

2. Women’s struggle for Papuan Independence

This powerful painting is by Emiria Sunassa (1895-1964) from north Sulawesi, the only female member of the influential Indonesian Painters Association founded in 1938. A sultan’s daughter of the spice-age kingdom of Tidore near Papua, she was actively involved through the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s in struggling for Papuan independence from the Netherlands. Her work focuses on experiences at the margins of the conventional nationalist story: those of eastern Indonesians and of women. Her works, like this one called Market, are full of tension and unease, dominated by dark hues and unsettled figures.

This powerful painting is by Emiria Sunassa (1895-1964) from north Sulawesi, the only female member of the influential Indonesian Painters Association founded in 1938. A sultan’s daughter of the spice-age kingdom of Tidore near Papua, she was actively involved through the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s in struggling for Papuan independence from the Netherlands. Her work focuses on experiences at the margins of the conventional nationalist story: those of eastern Indonesians and of women. Her works, like this one called Market, are full of tension and unease, dominated by dark hues and unsettled figures.

3. Mataram Batik Sarongs from Banyuwangi

Three batik tulis sarongs from Banyuwangi on the eastern edge of Java. They have distinctive local features: the gajah oling motif that looks like an elephant’s (gajah) curling trunk or, alternatively, an eel (oling); and the paras gempal (“crushed leaves”) background of the middle sarong. The colour palette is quite conservative and shows the strong influence of Yogyakarta, although there are elements of North Coast style in the way vegetation and animals are depicted. This stylistic mixture might be related to the fact that Banyuwangi was culturally linked to the pasisir (coastal) regions of East Java, but also spent much of the 17th century under the domination of the inland kingdom of Mataram (present-day Yogyakarta).

4. “Revelation Shadow Puppetry”

Indonesia has been a religiously diverse place for almost as long as we have historical records. Shaiva, Buddhist, Muslim, Christian, Confucian and many other religious practices have a rightful place in the country’s cultural life. Wayang shadow puppetry is a good illustration of this diversity. Wayang was initially used to depict the Indian stories of Rama and of the Bharata war. With the emergence of Muslim states in the 16th century, wayang puppetry adopted Arabic and other Muslim stories into its repertoire. Christian Javanese created a new genre called wayang wahyu (“revelation puppetry”) in 1960, as a means of communicating Bible stories in familiar performance idioms. This particular puppet traditionally represented the mountain at the centre of Indic cosmology, but in this interpretation, the crucified Christ takes that central role.

Jarrah is a Balinese-Australian and lecturer at the University of Sydney. His research interests include the traditional historiography of Southeast Asia, as well as the 20th century history, modern literature and regional popular music of Indonesia. Jarrah was a 2015 CAUSINDY delegate.